May 22, 2025

AI and copyright - will proposed legislation destroy the foundations of the UK’s creative sector?

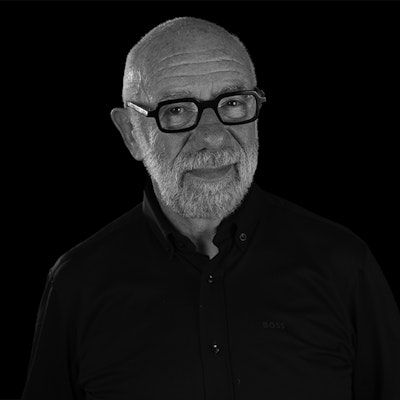

Film and TV lawyer Tony Morris reflects on the latest defeat of the Labour government’s attempt to enable AI companies to use existing copyright work without the permission of rights owners.

Failure to uphold the integrity of intellectual property and creators’ rights and to support those who finance and facilitate the ability of creatives to develop and communicate their work to the public could lead to the erosion of the sustainability of the creative industries.

Last week in the House of Lords, the UK’s upper chamber legislature, peers inflicted a third consecutive defeat of the Labour government’s attempt to enable AI companies to use existing copyright work without the permission of rights owners.

In December 2024, the government published a consultation paper. The paper’s stated objectives are “[to support] rights holders’ control of their content and the ability to be remunerated for its use”, while at the same time “supporting the development of world-leading AI models in the UK by ensuring wide and lawful access [emphasis added] to high-quality data.”

What, on the face of it, look to be complementary objectives would be meshed together by the government’s aim to “promote greater trust and transparency” between the creative sector and the AI developers.

The detailed aims espoused in the paper are worthy but it is apparent from the debates at Westminster that the extent to which wholesale ‘access’ is sought to be made ‘lawfully’ available to the AI developers could strip away the extent to which copyright is currently protected and consequently threaten the foundations on which the creative industries have developed. Specifically, the paper proposes introducing a new exemption in copyright law that would permit tech companies to train their AI models on all and any copyright works, including films, television and other audio-visual programmes and sound recordings without permission; the proposal would require creators and copyright owners to actively opt out.

Seemingly little thought has been given as to how the opt-out would work in practice. Practical issues are not difficult to imagine with literally millions of literary, dramatic, artistic and musical works already in existence and protected by English law; additionally, works created from around the world are subject to reciprocal protection in the UK afforded by international treaties. With no central database of copyright in the UK and little use made of the Library of Congress’s register in Washington, how would copyright owners indicate to AI developers that they were opting out?

The obvious riposte to the government’s proposal is that AI companies should notify copyright owners of a desire to use a work and to request consent, for which the owner may then charge a fee. It’s the way things have worked for more than a century, so why the need to change it now?

Whether something other than market forces should determine the basis for assessing use fees is another issue that doesn’t yet seem to be clearly within the focus of the legislators. It’s a secondary question that may yet assume even more significance than the primary one of the right to train.

The government’s paper contends that “At present, the application of UK copyright law to the training of AI models is disputed.” And that “AI developers are similarly finding it difficult to navigate copyright law in the UK, and this legal uncertainty is undermining investment in and adoption of AI technology.”

Existing law provides that copyright infringement arises when unauthorised use is made of the whole or of a substantial part of a copyright work. An AI developer using, for example, a photograph or a film protected by copyright without permission of the copyright owner to train an AI model not only infringes that copyright but may also infringe the moral rights of the authors. Rather than recognise that simple reality, already embedded in law, and support copyright owners’ entitlement to be remunerated for the use of their work, the proposed new legalisation turns established principles on their heads. Instead of requiring AI users to seek permission, it envisages providing the AI developers with a carte blanche right to use existing works and shift the onus on the copyright owner to ‘opt out’

At each reading of the Data (Use and Access) Bill, there has been an increase in the House of Lords majority supporting an amendment for a commitment to introduce transparency requirements ensuring, at the very least, that copyright holders can see when their work has been used and by who. This clearly reasonable proposal, consistent with the stated objectives of the government’s paper, has been voted down by the Labour majority in the House of Commons. The government seems to be doggedly supporting the preferences of the AI development community for an unfettered right to train and, if not ignoring the integrity of copyright, then to pay it not much more than lip service.

The Lords have engendered wide-ranging support from the creative sectors, including the British Film Institute (BFI), whose director of external affairs and deputy CEO, Harriet Finney was recently quoted in Screen Daily as saying, “Copyright is the lifeblood of the creative sector; it underpins its economic growth and our screen culture. We support strengthening the copyright framework to require licensing in all cases, alongside a commitment to transparency measures, so that UK producers, writers, directors, and performers can fully exploit their copyrighted works and catalogues”.

Rock and roll royalty, including Sir Elton John and Sir Paul McCartney, have spoken out against government proposals and implicitly support the Lords’ initiative which is being led by Baroness Beeban Kidron who has said that “The Government have got it wrong. They have been turned by the sweet whisperings of Silicon Valley”.

Organisations operating within the television sector, including All3Media, Banijay UK, the BBC, Channel 4, Fremantle, ITN, ITV and Sky recently issued a statement through PACT calling for greater safeguards for the integrity of copyright: “We believe that AI developers should not scrape creative sector content without express permission and that a framework that supports licensing of copyright content for AI training is the best way for the UK to share in the opportunity created by AI.”

In doggedly pursuing what is perceived as unconditional support of the AI giants, the government not only risks alienating the creative sector but, in enabling the wholesale plundering of its assets, may also undermine the basis on which that sector was able to contribute approximately £124 billion in gross value added to the UK economy in 2023. The creative sector also employs around 2.4 million people, accounting for about 7% of the UK workforce. Additionally, the creative industries are a key driver of UK exports, with goods and services worth £54.7 billion exported in 2021.

At this stage, whether or not the government will take any notice of the broad-based opposition to its proposals and rethink them is hard to know. Common sense suggests that it should, though the dictates of policy may not permit it to do so.